In the past decade, tech companies became ubiquitous not only in our daily lives but also in the global economy. By the beginning of the 2010’s the list of largest companies in the world as measured by market capitalisation was dominated by oil producing companies and financial services.[1] In 2019 however, seven out of the ten largest companies in the world are tech companies.[2] Along with rising economic power, their public image has shifted.

Digitization and the ‘sharing economy’ once went hand in hand, promising a new and better society. Inspired by San Francisco’s hippie culture, the entrepreneurs of Silicon Valley portrayed an image of do-gooders. But how did we get from the cozy sharing platforms of the early days of the internet to the imposing and omni-present corporate platforms of today? We show that they are a logical result of the forces at work in the platform economy.[3] And these same forces lead these tech companies into the financial sector in search for (personal) financial data.

This blog is part of a series in which we consider platformisation and its implications for the financial sector and for society as a whole. In this post, we look at how the platform economy works. We walk through the basic processes, how they are used to gain market share and how they result in ecosystems of platforms.

The first blog about the imminent platformisation of the financial sector can be found here.

What are the basic platform processes?

A good starting point for describing the platform economy is its three primary processes of datafication, commodification and selection.[4]

Datafication

In datafication, human actions are turned into datapoints that carry information relevant to the platform. When using a platform you leave a footprint of data by liking, befriending or simply watching your screen. Your likes, friends and scroll behaviour say something about your interests, social circle and what’s on your mind. Even when you do not use a platform itself, a platform establishes links with websites and apps to harvest data.

Financial processes are already to a large extent subject to datafication as electronic exchanges of money leave data trails. In the Netherlands, the share of electronic payments (as opposed to cash) in all transactions increased from 32% in 2010 to 63% in 2018 source?. Although transactions become increasingly datafied, this is not the result of a platform process (yet). Not the desire to collect consumer data, but ease of use, increased safety and cost efficiency were named as the main reasons for entrepreneurs and banks to work together in an extended campaign to promote the use electronic forms of payment.[5] Other interests should not be viewed in isolation from this trend, though. An increased proportion of electronic payments contributes to limiting tax evasion and whitewashing. Still, this is no platform process, but that could change quickly. The GAFAM (Google, Amazon, Facebook, Apple & Microsoft) platforms are all active in payment services.[6]

Commodification

A platform turns data into marketable goods and products or, in other words, turns it into a commodity. Commodification is best expressed through the personal profile that is created from the collected data points. The personal profile is used in whatever way it is most profitable to the platform. The personal profile can be used to sell targeted advertising space, influence public opinion or assess credit risk.[7] Profiling and targeting follow the sequence: hindsight – insight – foresight. Based on historical datasets (hindsight) patterns are identified (insight) and applied to predict (foresight) and steer (tuning, herding and conditioning) user behaviour.[8] To provide a sense of the scale of commodification: in 2016 Facebook used at least 52.000 behavioural attributes to classify users, ranging from ‘age’ and ‘gender’ to the more predictive ‘pretending to text in awkward situations’ or ‘breastfeeding in public’.[9]

Privacy regulation and commodification are at odds in the financial sector as is illustrated by the case of ING. In 2019, the bank, in changes to its privacy statement, made known its intent to use bank data for personalized advertisements. This led to the Dutch Data Protection Authority (NL: AP) reminding the banks of the rules for data sharing and warning them against privacy abuse. As a member of the AP-board stated: “Payment details provide a complete picture of someone’s life: what you spend your money on, which associations you belong to, who you associate with, which patterns are visible? That is why the AP considers it important to point out the privacy rules to the banking sector.” According to those rules, banks can only use data for the purposes for which they were initially collected, unless explicit consent of the consumer is obtained.[10]

New forms of inequality may emerge as a result of commodification. A recent poll by Dutch platform engineering firm TJIP shows that a large portion of consumers is willing to give insight in their financial data in return for a lower interest rate on their mortgage.[11] Paying less money for housing may seem like an appealing offer, but giving up privacy instead sounds less attractive. An economy-wide trend of payment with data can bring about a split between people who can afford privacy and those who cannot.

Selection

Datafication and commodification feed selection, which is the process of determining what you see on your screen. This process manifests itself, for example, in the web pages that show as a result of your search, the articles in your news-feed and suggestions for new connections. Most of the selection process is automated by means of algorithms.[12] Although the computer makes the decision, algorithms are made by people. They carry, therefore, the values of the people that design them and serve the interests of the organisation that operates them. The most intelligentalgorithms are self-learning and thus not made by people and influenced by their values? and therefore change constantly. Algorithms that are essential to the workings of a platform are often considered a competitive advantage and are secret. This combination of machine learning and restricted access have the consequence that very few, if any, people understand exactly how the algorithms work.

In financial services, the selection process can manifest itself in the form of tailor made financial advice. An algorithm searches for the loans, insurance products or energy provider that best suit your needs based on your transaction and behavioural data. A good example is Yolt, a bank account aggregation app. Most apps connected to this platform are comparison apps. FXcompared provides the best money transfer, Monevo matches your preferences for a personal loan and MoneySuperMarket lists the offerings of energy suppliers.[13]

Those apps provide tools that make the lives of consumers easier, but conflicts of interest present in traditional comparison tools apply equally to the new ones.[14] For instance, a tension exists between the profit motive and impartiality of advice. This tension is even more pronounced in the digital environment, where consumers are used to ‘free’ services. To gain market share, companies provide their core service at no cost which pressures them to look for alternative ways to make money. A profit-driven company might be tempted to push offerings that pay the highest commission.

As we see, it becomes harder to make the selection process transparent and assess the impartiality of a comparison tool when algorithms get increasingly complicated.

How do platforms gain market share?

Most platforms started with one core competency. Uber connected you to the nearest taxi driver. Spotify offered you music. Amazon sold you books. Datafication, commodification and selection, in combination with the profit motive, quickly drives platforms to become more than just a service company. Like any corporation, platforms seek to maximise profit. The notion of ‘more is better’ is strengthened by the existence of network externalities. A network externality exists when there is a positive feedback loop between the quality and nature of a service and the number of participants on the platform. More users increase the value – for users and for the platform – of a social network or a market place. Or more relevant for financial players: more users generate more data which enhances the selection mechanisms of the platform.

Gaining momentum is extremely important for a platform. An essential feature of the business model of many platforms is therefore that its services are provided for ‘free’ to users. Any platform knows perfectly well that charging a fee will create a barrier for customers to join the platform. Of course, the service is not free. Customers pay with their data, which is turned into profitable use by the platform.

What does this mean for competition?

In addition to network effects, platforms have strong economies of scale and scope and enjoy very low marginal costs of production and distribution. Economies of scale are present as digital products often have fixed development costs but little or no variable costs for distribution. Thousands of additional users can be added at very little costs. Economies of scope exist where complementary services can readily be introduced. Moreover, a wider variety of data sources means a richer dataset. This makes financial data of specific interest to large tech companies, as financial data is not yet part of their data stock.

The combined result of those features is the creation of a ‘tipping point’ in digital markets. At a certain moment a company reaches a position when economies of scale and scope automatically leads to its dominance. To win, tech companies do not compete in the market, but for the market. [15] Platforms do not shy away from aggressive pricing. E.g. Uber reportedly charges customers only 41% of the full costs of a taxi.[16] Those costs can be earned back once dominance is established. Booking.com, today, charges 10 to 25% on each hotel booking and Takeaway.com increased its fees from 6% in the Netherlands in their early days to 13% in 2018.[17] Striving for a monopoly is inherent to Silicon Valley model, as is reflected in the words of venture capitalist Peter Thiel: “Competition is for losers”.[18]

This year, competition in Europe became more open when the Second Payment Service Directive (PSD2) came into force. Banks are now required to share financial data with third parties when a customer allows it.

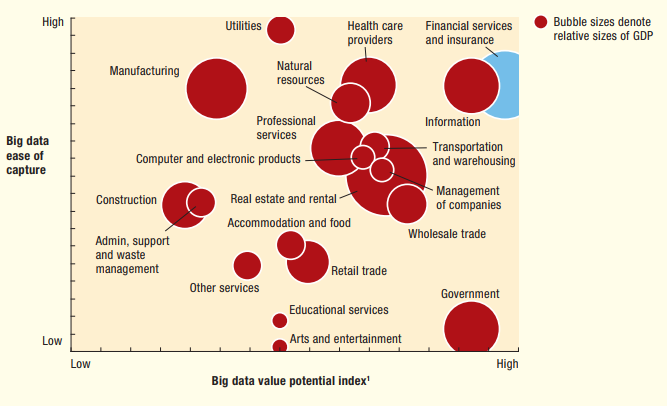

There is great value potential in applying artificial intelligence to financial data (e.g. fraud detection, automated credit scoring, and increased customer responsiveness), likely to result in better products for a lower price.[19] As is evident from the figure below, the value potential and the ease of capture for financial services and insurance data are both high. It is, then, not surprising that Google, Apple and AliPay all have PSD2 permits.

1: The value potential and the ease of capture for big data and advanced analytics is especially large in financial services[20]

How does a platform become an ecosystem?

Economies of scale and scope lead platforms to expand into other markets. Existing datasets create a competitive advantage because they already provide valuable customer insights. Users of the existing platform can be guided into a new platform by the seamless connection with their user account, default hardware settings or by targeted advertisement. The resulting set of platforms combines a wide range of functionalities into what is called an ‘ecosystem’.[21]

Vertical and horizontal integration pays off. Alphabet, for instance, provides a browser (Chrome), operating system (Android), email (Gmail), video broadcast (YouTube), search engine (Google) and app store (GooglePlay) to name just a few of their services. And all of its data is stored in its own datacentres. In a similar fashion, ING wants to become the “… go-to platform for financial needs and services beyond banking.”[22] Next to bank accounts, mortgages and insurance it creates new digital products like the financial planning tool ‘Kijk Vooruit’ (EN: ‘Look Ahead’) and cooperates with fintechs in Germany and the UK.

The reason for this abundance of services lies in the wish to collect data. As Shoshana Zuboff describes in her book ‘The Age of Surveillance Capitalism’, all those apps provide the supply of the commodity on which platforms run, which is data. They have a goal of: “…continuous expansion of the extraction architecture to acquire raw material at scale to feed an expensive production process that makes prediction products that attract and retain more customers.”[23] Hence, the great interest of technology companies in wearables, smart home appliances and cooperation with cities in urban planning.[24] All those appliances can eventually be used to predict and influence behaviour. Needless to say, prediction and influence are not only a great money maker but are also a potential source of political power.

How is this relevant to the My Financial Data-project?

We have seen that the value potential of platformisation is especially big in the financial sector. As the financial sector becomes more datafied, the application of artificial intelligence becomes more beneficial — this is low-hanging fruit for tech-savvy firms. We have also seen that extensive data collection for behavioural prediction and conditioning is central to the platform business model. Adding financial services to an ecosystem can greatly enrich profiles and increase the platform’s capability to predict and influence the consumer’s behaviour.

The objective of the My Financial Data-project is to enable a new kind of platform economy in the financial sector where not the profit motive, but consumer value is the most important factor. Financial data should not fall into the hands of exploitative Big Tech platforms or hypercommercial banks, and we should not look only to the state for regulation.

The My Financial Data-project seeks to research the best way of establishing a cooperative platform for financial data in which its users work together to determine how their needs are served best. So that they are able to safely open up their sensitive data to financial service providers in a platform ecosystem that is controlled by themselves.

What’s next?

In the next blog we look at the impact of the platform economy on

society. Should we view Big Tech as the new robber barons? What is the

difference between the Chinese and the Silicon Valley approach to platforms?

What types of legislation can be put in place?

This blog is written in collaboration with Cormac Petit.

Also in this series:

[1] Financial Times (2009). The Financial Times Global 500 – 31st December 2009

[2] Forbes (2019). The World’s Largest Public Companies – 26th May 2019

[3] Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books Ltd. & Bartlett, J. (2018) The people vs. tech: How the internet is killing democracy and how we save it. Ebury Press Zeker ook Zuboff betrekt deze stelling

[4] The descriptions of the platform processes of datafication, commodification and selection are based on ‘Van Dijck, J., Poell, T., De Waal, M. (2018). The platform society: Public values in a connective world, Oxford University Press’.

[5] The ‘Stichting Bevorderen Efficiënt Betalen’ (EN: Foundation to Promote Efficient Payment) considered its goal to be reached and disbanded in 2018. Their activities are from 2005 until 2018 are described in ’13 jaar werken aan efficient betalingsverkeer’.

[6] FSB (2019). FinTech and market structure in financial services: Market developments and potential financial stability implications, FSB Report

[7] WeBank in China uses social media data from its parent company Tencent to assess credit risk for loans without collateral. See p14 of Accelerating Financial Inclusion with New Data, by IFF and CFI-ACCION.

[8] Tuning, herding and conditioning are three forms of behavioural manipulation as described by Shoshana Zuboff in The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power (2019). ‘Tuning’ refers to subtly shaping consumer behaviour through the choice architecture. ‘Herding’ is forcibly closing choice options as to herd consumers to a predefined action. ‘Conditioning’ means structurally changing someone’s behaviour.

[9] Based on research done by ProPublica. The article can be read via https://www.propublica.org/article/facebook-doesnt-tell-users-everything-it-really-knows-about-them.

[10] Autoriteit Persoonsgegevens. 2019. Guidance voor uw leden over de verdere verwerking van transactiegegevens voor direct marketing-doeleinden. Letter to NVB. 1 july 2019.

[11] Haverkamp, K. (2019). Twintiger best bereid om data te delen in ruil voor hypotheekkorting. TJIP

[12] A good description of what an algorithm is and what it does is provided by Lifewire via https://www.lifewire.com/what-is-an-algorithm-4153813.

[13] https://www.yolt.com/connect.

[14] European Commission. 2013. Study on the coverage, functioning and consumer use of comparison tools and third-party verification schemes for such tools

[15] Chicago Booth. (2019). Market structure and antitrust subcommittee report. Committee for the Study of Digital Platforms.

[16] Via https://ftalphaville.ft.com/2016/12/01/2180647/the-taxi-unicorns-new-clothes/.

[17] The commission for Booking.com can be found on their website https://partner.booking.com/en-gb/help/commission-invoices-tax/how-much-commission-do-i-pay. The increase of the percentage that Thuisbezorgd.nl charges its business customers is reported on Dutch newssite NOS via https://nos.nl/artikel/2205086-restaurants-boos-thuisbezorgd-zet-commissieverhoging-door.html.

[18] Peter Thiel. (2014). Competition is for Losers. Wall Street Journal.

[19] McKinsey & Company. (2016). Beyond the Buzz: Harnessing machine learning in payments, McKinsey & Company paper

[20] McKinsey & Company. (2016). Beyond the Buzz: Harnessing machine learning in payments, McKinsey & Company paper

[21] ING Group. (2019). 2018 ING Group Annual Report.

[22] Quoted from the CEO statement in the 2018 Annual Report of ING.

[23] Zuboff, S. (2019). The age of surveillance capitalism: The fight for a human future at the new frontier of power. Profile Books Ltd.

[24] Alphabet’s sister company Sidewalk Labs is collaborating with the city of Toronto to redevelop a neighbourhood as a ‘smart city’. Via https://www.sidewalktoronto.ca/.